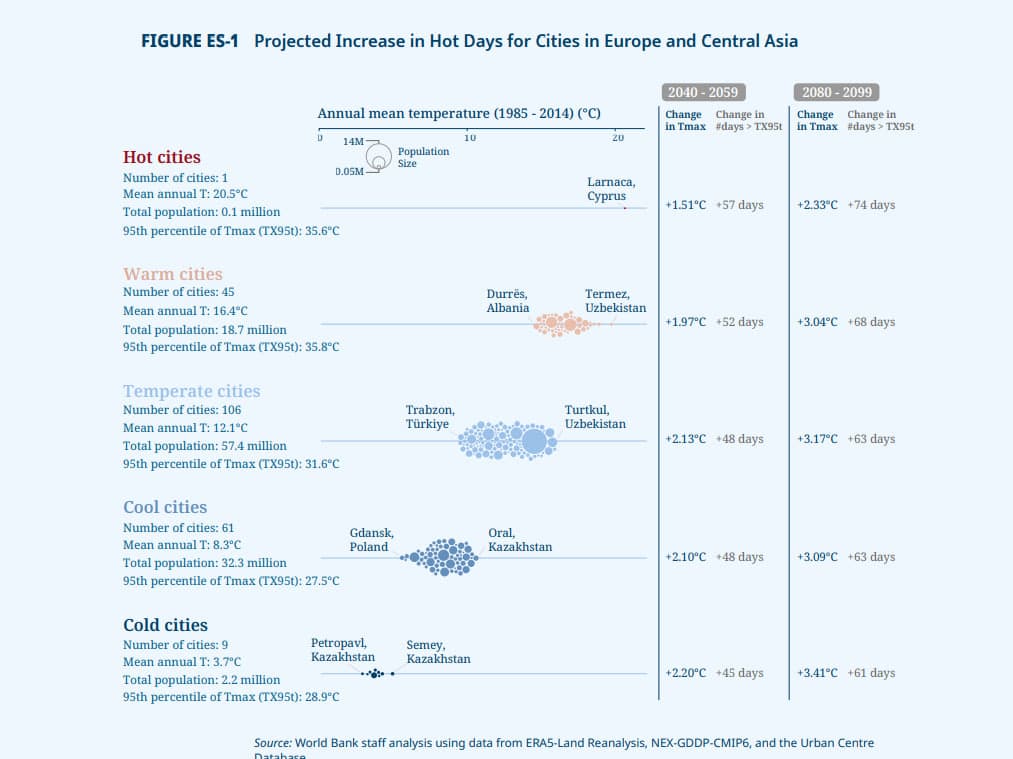

Cities across Central Asia are experiencing rising temperatures, with forecasts suggesting the number of hot days could triple by mid-century, World Bank reports. By 2050, major cities in the region may face an additional 40 to 70 hot days annually, posing a serious threat to health, infrastructure and economic stability.

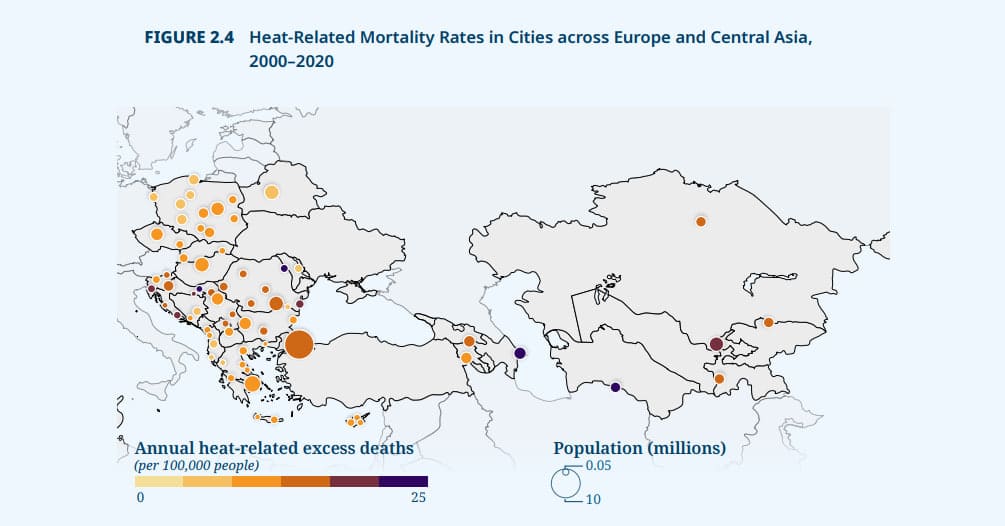

Over the past two decades, heat-related fatalities have already reached tens of thousands across Europe and Central Asia. This number is expected to double or even triple in many urban areas, placing it on par with fatalities caused by road accidents. Older adults and lower-income communities will be among the hardest hit, as extreme heat exacerbates chronic health issues and leads to spikes in emergency room visits that overwhelm public hospitals.

Economic losses and collapsing systems

The economic toll is expected to be severe. In some parts of the region, especially Central Asia, heat-related losses could amount to 2.5% of GDP by mid-century. As temperatures rise, productivity falls. Outdoor industries such as construction, transport and tourism are particularly vulnerable, as workers slow down, reduce hours or cease operations entirely. Meanwhile, critical systems—like energy grids and transport networks—are increasingly at risk of failure.

Much of Central Asia’s existing infrastructure, largely built during the Soviet era, is ill-equipped to handle prolonged heat stress. Droughts are intensifying, wildfire risks are rising, and air quality is deteriorating, further compounding the public health burden.

Cities can act now, but financing remains a challenge

Despite these risks, there are solutions. Cities can reduce urban heat by planting more trees, expanding green spaces and introducing shaded areas. Public health can be protected through early warning systems, dedicated cooling centres and better heatwave preparedness. Infrastructure can be adapted by retrofitting schools, hospitals and housing to better regulate indoor temperatures and withstand extreme conditions.

Promising innovations are already emerging. Some cities are developing heat vulnerability maps to guide investments, while others are aligning heat resilience with transport, housing and public investment strategies. Performance-based financing is also being piloted to reward municipalities for proactive measures.

However, financing remains a major barrier. Without new mechanisms to bridge the funding gap, even the most well-intentioned plans risk falling short.

A successful response hinges on local action within a coordinated framework. This requires clear institutional roles, stronger municipal capacity and the integration of heat resilience into everyday governance—from zoning laws and city budgets to healthcare planning. Central Asia, in particular, must act swiftly to build a heat-resilient future before the costs become unmanageable.

Kursiv also reports that Uzbek developer has proposed a review of Uzbekistan’s current moratorium on tree cutting.