Over the past decades the Aral Sea has retreated 140 km from Muynak and now the town has to adapt to life without the sea. Today Muynak differs little from other small towns of Uzbekistan, except for its unique history.

Only the rusty hulls of ships on the former shore, old maps of the Aral and a preserved anchor remind of its maritime past. In the Museum of the Aral Sea guests are shown a black-and-white film about the full waters and the fishermen.

The realisation of the catastrophe comes when one leaves the museum. Before you is a vast desert. It is hard to believe that once water splashed here, boat engines rattled and fishermen pulled their catch from the nets. The air was filled with the smell of fish and the hum of ship sirens spread over the town.

Now Muynak is home to about 15,000 people. They preserve the memory of the past and get used to the present.

Kursiv Uzbekistan spoke with the residents of Muynak and learnt their stories, dreams and everyday concerns.

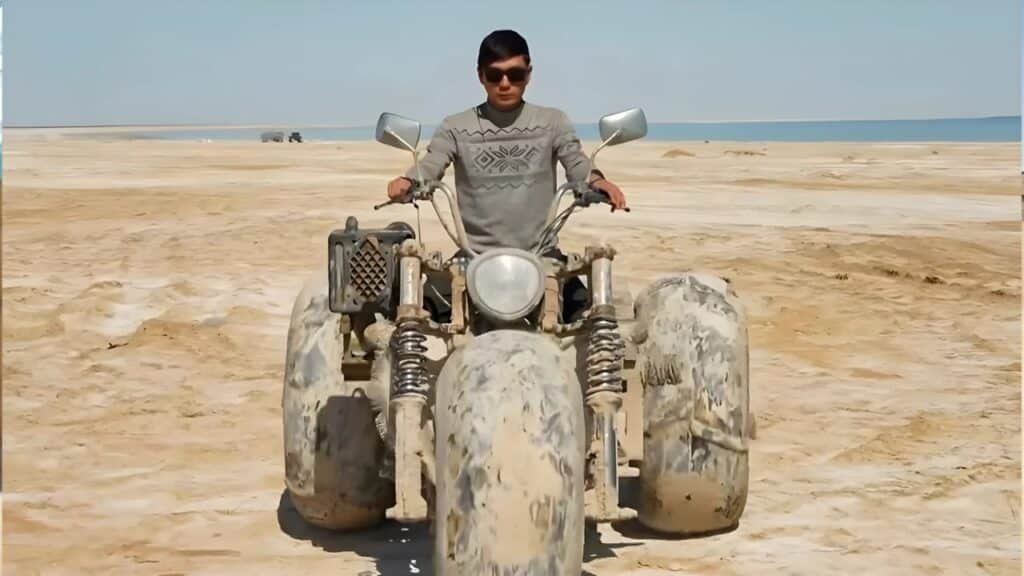

Artemia Instead of Fish: The Story of Nursultan

Nursultan Utemisov rides along the shore of the Aral Sea on a homemade motorbike. The water is very close, but it is difficult to reach it — the seabed has only recently been exposed and has not yet had time to dry, turning into sticky mud.

His motorbike has wide tyres, only these can pass through this mire. A car or an ordinary motorbike would immediately get stuck in the dirt. Nursultan walks along the shore only in boots because the unstable ground quickly swallows.

Nursultan is 20 years old, he is from Muynak. This summer and autumn he works in a yurt tourist camp on the shore of the sea. The whole camp is ten yurts, another ten are planned to be set up.

In the camp Nursultan spends six days a week, one day he goes home into town. During this time his colleague replaces him. He mainly communicates with his family via Telegram and WhatsApp.

He is glad that he managed to find work, as in Muynak there are almost no other opportunities.

«Tourists come to us from China, South Korea, England and France. They often ask if they can swim in the Aral Sea. I reply that no one forbids it, but I warn them that the water is too salty,» says Nursultan.

A night in a yurt with full board costs 45 euros. Fish is served for dinner, but it is brought from Muynak, for in the Aral Sea there has been no fish for a long time. Electricity in the camp is produced by generators. Drinking water appeared only this year and it is delivered from a well 180 m deep.

When the tourist season ends Nursultan switches to another occupation. He catches artemia, small crustaceans living in the salty waters of the Aral. These crustaceans are bought by Chinese companies which make protein supplements from them. The catch continues from the beginning of winter until the end of March.

Last Marine Artist of Muynak: How an Artist Paints the Sea That No Longer Exists

Anuarbek Saimbetov is the only artist and sculptor in Muynak. He is 78 years old, almost his entire life has been connected with the sea that no longer exists. In his paintings is the Aral as he remembers it.

In his childhood the sea was everywhere. «Wherever you looked was water with almost no land,» he recalls. From home to the shore it was 200 metres.

His father was a fisherman, his mother kept the household and did handicrafts — embroidered suzani, wove carpets, decorated household utensils. The children grew up among boats and water: even to the shop or library they travelled by boat.

He especially remembered the library. The librarian always greeted the children with magazines which they read for hours and then played chess and draughts. It was the illustrations in the magazines that first inspired Anuarbek. He saw the sea on the pages and tried to recreate it on paper.

When Anuarbek was in the sixth grade, a Moscow artist came to Muynak. He gave paid lessons and the boy became his pupil.

After school the choice was between university or the sea and he chose the sea. He completed courses for ship navigators and received a certificate allowing him to work on any vessel.

Anuarbek served in Tselinograd (now Astana) as a driver, transporting grain. But even in the army he did not part with his sketchbook. Once his commander saw the drawings and the driver became the unit’s designer-artist.

When he returned home, he discovered that the sea had gone. The profession of navigator was no longer needed. Then he finally chose art as the memory of the Aral became his main source of inspiration.

Today Anuarbek paints the sea that no longer exists to preserve it for children and grandchildren. In every painting there is sadness for what was lost and hope that the sea will return.

He is inspired by Aivazovsky and Bogolyubov: The Ninth Wave reminds him of a storm he experienced on the Aral, and Entrance of a Fishing Boat into the Harbour of ships leaving Muynak for the sea.

How a Forestry Specialist from Muynak is Turning the Aral Seabed Green

Alisher Bekmuratov is 38 years old, he is from Muynak. His childhood passed among the sands of the Aralkum: with friends he ran barefoot and played hide-and-seek, hiding behind bushes of saxaul and dzhingil.

«At that time there were only these plants and very few others. The wind lifted dust and sand which sometimes completely covered the entire village. Then scientists realised that it was necessary to create a forest in the desert to protect people,» recalls Alisher.

After school Alisher decided to fulfil his dream of becoming a forestry specialist and taking part in replanting the bed of the Aral. While many of his classmates left for other towns and countries, he went to Nukus to study at the faculty of forestry. In 2006 he returned to Muynak and began working in his profession.

Alisher’s working day begins in the nursery — here saplings are grown for the future forest on the bed of the Aral.

They grow trees and shrubs that can survive in desert conditions: poplar, elm, juniper, willow, saxaul, kandym, dzhuzgun and others. These plants stop the movement of sands, clean the air and protect people from dust storms.

«In the last five years planting has been carried out on 1.9 mln hectares, more than 1 mln hectares are already covered with forest. I am glad that I was able to make my contribution to this work,» says the specialist.

The desert is in no hurry to surrender the captured positions. Progress is slow and requires great effort. But the first changes are already noticeable: artesian waters have begun to break through from underground, reeds have grown in these places, and then birds and wild animals have returned — hares, wild boars, saiga, wolves and jackals.

Young people are actively joining the planting. Every autumn in October and November students and schoolchildren from Nukus, Muynak and other districts go out onto the bed of the Aral to plant trees.

«The harsh desert does not give up at once. We still have much work ahead, but new greening technologies give hope. One wants to believe that the bed of the Aral will become green,» says Alisher.

The Story of the Woman Who Opened the First Hotel in Muynak

A flight from Nukus to Muynak in a small plane takes only 30 minutes — instead of 2.5–3 hours along the broken highway. From the window passengers see familiar villages and saxaul forests. For now there are few flights, but even these have already noticeably simplified travel to the remote district.

For Dilfuza Kutlimuratova Muynak became home and workplace. After staff cuts in the education system in 2016 she decided to go into tourism and moved from the capital of Karakalpakstan to the town where new opportunities were just beginning to appear.

Together with entrepreneur Amina Begzhanova Dilfuza rented an old building from 1934 and with her own funds carried out repairs. Amina’s experience in tourism and hotel business helped to set up the work properly. This is how the town’s first hotel with 25 places appeared.

«We started from scratch: repairs, improvements, gradually the first guests began to arrive,» she says.

Today Muynak is becoming a point of attraction for tourists from different regions of Uzbekistan.

«Folklore groups and food bloggers come to us. Before they showed only the museum and the ‘ship graveyard’, now tourists are offered much more — music festivals, excursions and dozens of fish dishes,» she says.

She notes that many tourists are struck by the tragedy of the Aral: some of them know almost nothing about this ecological catastrophe.

The developing tourism faces many problems, the main one being transport accessibility. Main Nukus–Muynak highway is badly worn out: only cars can drive along it, buses cannot pass. The road from Muynak to the sea, about 140 km, also remains unsafe.

«For tourism to develop, new air routes and good roads are needed — only then will Muynak truly become accessible,» says Dilfuza with confidence.

The Aral Region Today: Consequences and New Projects

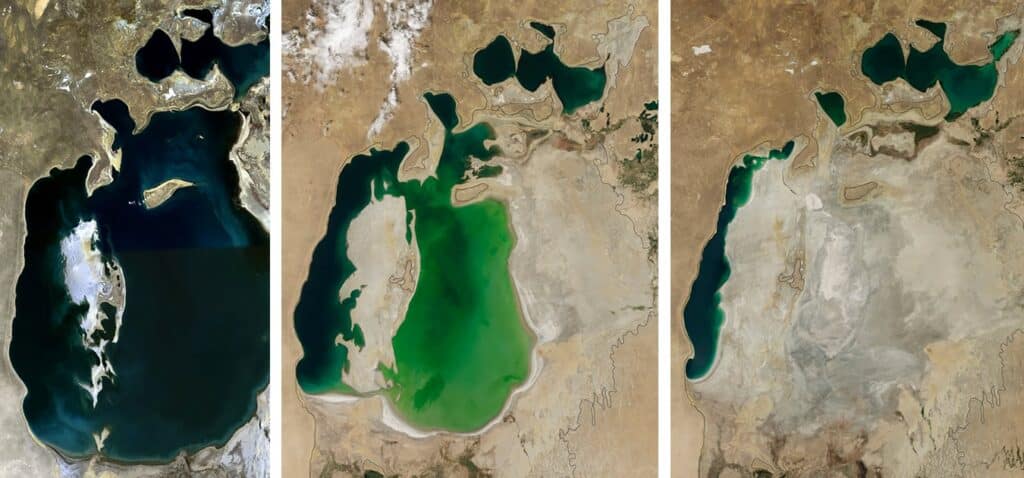

Until the 1960s Aral was the fourth largest lake in the world. Its area was 69,000 sq. km, it was fed by the rivers Amu Darya and Syr Darya.

The sea gave life to tens of thousands of people who were engaged in fishing and navigation.

However, in the mid-20th century due to large-scale water withdrawal for irrigation the sea began to shrink rapidly. By 1989 the Aral had divided into the Northern and Southern parts.

By 2014 its area had shrunk to 10% of the original, on the site of the water body arose the Aralkum desert, covering more than 6.2 mln hectares (3.4 mln in Uzbekistan and 2.8 mln in Kazakhstan).

This catastrophe destroyed fishing and ports, thousands of people lost their jobs. The main disaster became salt and dust storms from the dried seabed, carrying toxic dust for hundreds of kilometres and causing damage to the environment and health.

«The Aral must become a lesson of how not to treat natural resources,» says Vadim Sokolov, head of the agency for the implementation of projects of the International Fund for Saving the Aral Sea in Uzbekistan.

According to him, restoration is progressing with difficulty. More than 2 mln hectares of territory are covered with forestry works, but only 600–700 thousand hectares have actually taken root.

The development of the region is not limited to greening. On the Ustyurt a polyethylene production plant has been launched, which made it possible to establish domestic production of water-saving systems, including for drip irrigation, making them twice as cheap as imported ones.

On the bed of the dried sea the gas condensate field «Aral-1» is also being developed.

Tourism remains a promising direction. The unique landscapes and history of the Aral Sea attract travellers from all over Uzbekistan and abroad.

In addition, traditional activities are developing in the region — the harvesting of artemia used for protein supplements, the gathering of liquorice in demand in the food and pharmaceutical industries.

These projects give the Aral region momentum for development, and the people living here jobs and hope that this land, which lost its sea, will again become a place where one wants to live and stay.