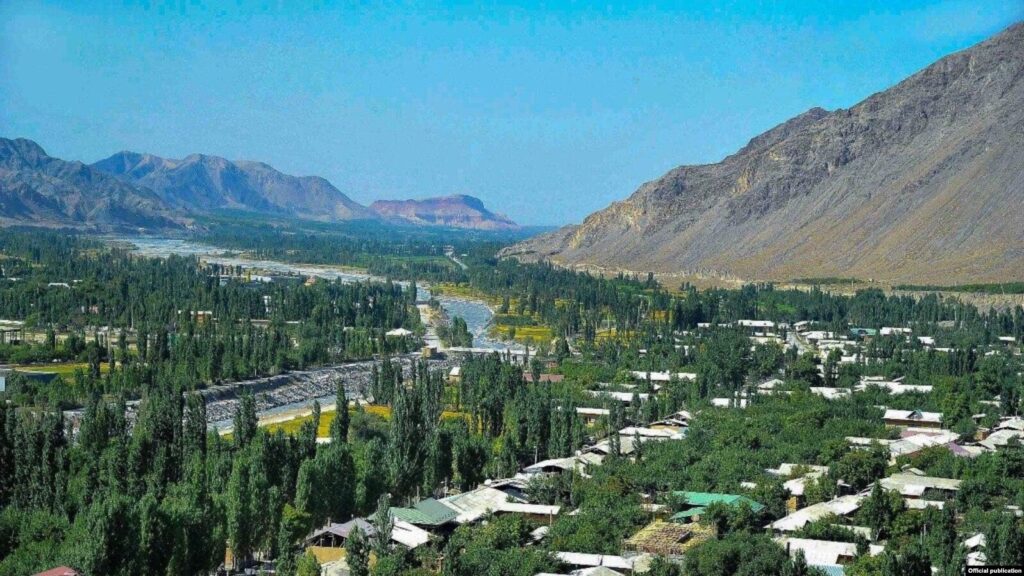

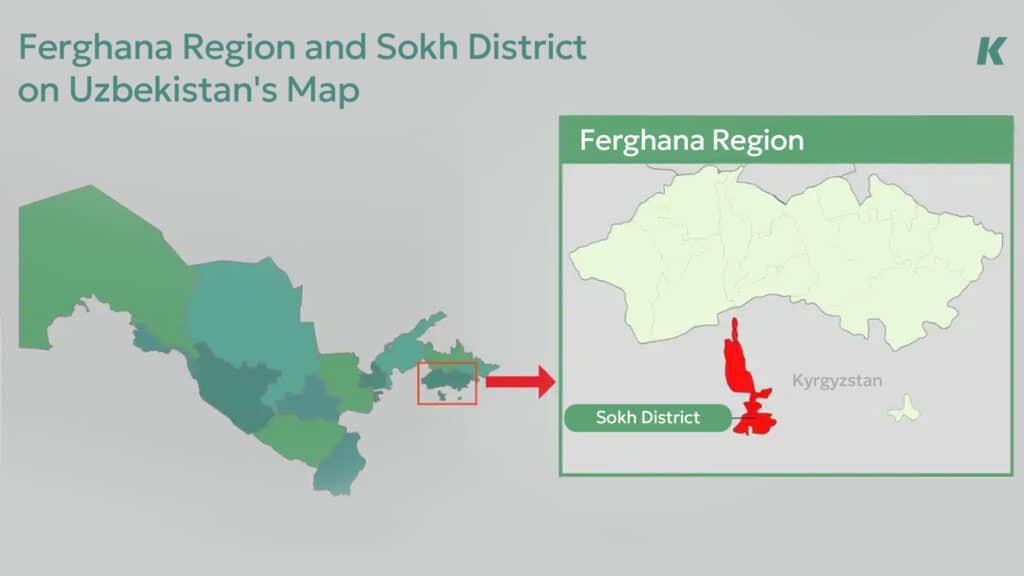

Sokh is an Uzbek enclave in the mountains of Kyrgyzstan where 87,000 people live on a small patch of land. Potatoes, maize and a unique variety of saffron are cultivated here, while residents cross the border daily for study, work and trade.

After a border clash over water with a neighbouring Kyrgyz village in May 2020, the Uzbek government paid special attention to Sokh.

Since then, new roads, houses and schools have been built. Yet the status of an enclave still brings many difficulties, and the people of Sokh are waiting impatiently for solutions.

Kursiv Uzbekistan set out to discover how life in Sokh is changing, what people dream of and what kind of change they are hoping for.

The Time of Saffron

Dawn breaks over the mountain villages of Sokh. A fresh breeze carries the delicate scent of saffron growing on the slopes. This flower has only recently begun to be cultivated here, yet big hopes are pinned on it. From it comes a rare and precious spice.

Farmer Rashod Odilboev steps carefully between the rows, mindful not to damage the fragile petals. Saffron is his pride: he was the first to grow it in Sokh.

He once grew potatoes and corn. Over time he realised that even a small saffron plot could bring more profit than traditional crops.

«In 2022 I tried planting saffron in my garden, just 200 square metres of land. I read everything I could find about it online. When I sold my first harvest I understood there was a future in it,» recalls the farmer.

Encouraged, he took the next step. Local authorities allocated him 12 hectares of long-unused land. Five hectares are now planted with saffron, the rest waiting for the next sowing.

His cooperative employs 18 permanent workers, rising to 70–80 in the season. Flowers are picked, dried and cleaned by hand.

A new chapter has now begun for his farm — its first export contract with Kuwait. In mid-October a trial shipment of 20 kilograms of saffron will be sent to the distant Gulf state.

«When we first started there were so many obstacles. We would spend hours at the border while Kyrgyz guards and customs officers processed the papers,» Rashod says.

The situation is slowly improving. A new airport, simplified customs posts and better ties with neighbours have made farmers’ work easier.

«My dream is for as many farmers as possible to grow saffron. There is always demand for it,» he adds.

Indeed, Sokh’s mild climate and abundant water make it well suited for saffron cultivation.

Mountain Potatoes, Long Road

The sky is overcast. The autumn potato crop must be gathered quickly before the sudden mountain rains arrive. At 70 years old, farmer Subkhonberdi Mavlonov still goes out to the field with his workers.

The potatoes are bound for Fergana, Rishtan and Kokand. Most of the workforce are women. They collect the tubers, place them in 10–15 kilogram net bags and line them up at the edge of the plot ready for loading.

Subkhonberdi has worked the land for 25 years. His farm grows corn, carrots and onions, but potatoes remain the main harvest.

He sells directly to buyers. Reaching the markets of neighbouring districts is not easy since the border with Kyrgyzstan must be crossed.

«At the border documents are checked for hours. It’s exhausting and sometimes prevents us from delivering produce on time,» he says.

Water for his farm is generally sufficient, taken from a mountain river, with only occasional difficulties.

Subkhonberdi is convinced Sokh could feed the whole valley. But for that, he says, potato deliveries to other districts must be made easier.

Journey from Sokh: Learning to Preserve a Language

For Dilfuza Usmanova, the journey from Sokh to Fergana is more than just a road. To attend university classes she must pass through two Kyrgyz and two Uzbek checkpoints and travel some 30 kilometres across Kyrgyz territory. Border queues sometimes extend the trip by several hours.

Dilfuza is in her fourth year studying Tajik philology at Fergana University. After finishing school she chose to become a teacher of Tajik language and literature. In Sokh, such teachers are dwindling, while schools with Tajik-language instruction are few.

«I want children not to lose touch with their culture and mother tongue,» she says.

Dilfuza enrolled thanks to a state-funded grant for young people from Sokh. The programme, launched after the tragic events of 2020, offers 500 free places at universities across the country.

Thanks to the quotas, the share of students from Sokh district rose from 5% to nearly 30%. For girls from traditional families who cannot easily leave home, it has become a genuine chance to gain an education and a profession.

Media in Sokh: The Enclave Speaks for Itself

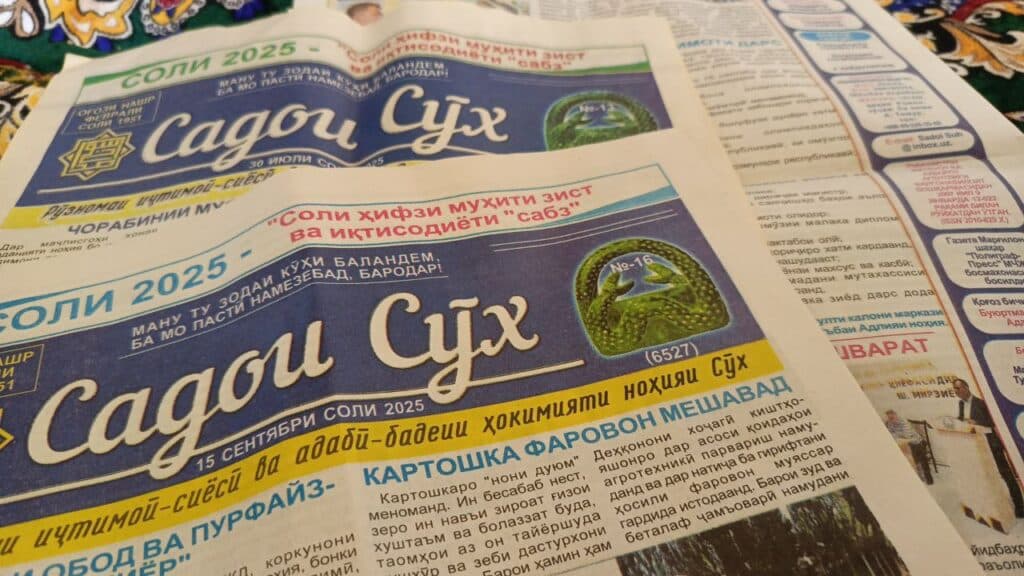

Sodik Tokhirov is editor of Sokh’s only newspaper, Sadoi Sokh («Voice of Sokh»). Its print run is 700 copies. At 64 Sodik is retired but continues working as there is nobody to replace him.

Young journalists are reluctant to join the newsroom because of low wages. The paper has been published for more than half a century and remains the main source of local news.

Sokh also has Sokh TV, broadcasting in Uzbek and Tajik. Its main correspondent, Jahongir Sobirov, keeps the rest of Uzbekistan informed about life in the enclave.

«The biggest problem in Sokh is youth unemployment. Many go to Russia to work and migrant remittances become the main income for families,» the reporter explains.

Some young families move to other regions of Uzbekistan. For those wishing to stay and farm, the government allocates land from 1,000 square metres to one hectare of land.

«We try to provide jobs this way. The issue is that there is no industry in Sokh,» says deputy hokim Muslimbek Mavlonbekov.

According to him, plans are in place to develop health resorts and agrotourism in the enclave.

Ties to the Mainland

In November 2021 Sokh welcomed its first pilot flight from Fergana. Now planes fly three to four times a week, though most travel to the mainland still takes place by road.

For serious treatment, medical tests or operations, residents must go to Fergana or Kokand. Even for clothing, household goods and fertiliser they must cross the border.

«There is a very short road to Uchkuprik district, just seven kilometres through Kyrgyz territory. It would be ideal to open a corridor and remove the checkpoints. Then travel for Sokh’s residents would become much easier,» says Mavlonbekov.

Still, some progress has been made. Since September 1 citizens of Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan can cross the border with national passports or ID cards, which has slightly eased the journey.